The sound of cars and street vendors on the busy Hebron road in Bethlehem, West Bank, seems to have disappeared. Besides the dumping ground, on the right side of the street, is the health department building from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). An angel painted on the walls of the building, which marks the entrance to Dheisheh refugee camp, seems to bring some peace to those who live there: Palestinian refugees within Palestine itself.

The Dheisheh camp, or Duheisha, was founded in 1949 as a temporary shelter for 3400 Palestinians from 45 villages of Jerusalem and Hebron that fled during the Arab-Israeli conflict in 1948. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, approximately 10.500 people were living in the camp in 2014 when the last census was taken. To the right, as you enter Dheisieh, which is structured in alleys and curving slopes, is the Ibdaa Cultural Center, a local non-governmental organization that works with projects for the well-being of children, youth, and rural women. A tall, brown man emerges from the organization’s door, with a thin nose and beard, typical Arab features, and opens a smile from ear to ear, his trademark. Palestinian refugee resident of Dheisheh and originally from the village of Al-Walajeh, Hamzeh Daggash Abbedrabu, 30 years old, is a social worker and psychologist who professionally works with children and adolescents in an international organization and voluntarily at the Ibdaa Center.

Hamzeh shares how his problems with living in a refugee camp started the day he was born. His mother was due to give birth on February 24, 1988, and at that time, the camp residents were under curfew orders due to the First Intifada. Dheisieh was completely closed off by soldiers, and no one could leave the house. Complications in childbirth prompted Hamzeh’s father to violate the curfew and go outside in search of a midwife. He went out in the cold, it was snowing, and he was stopped and threatened several times by soldiers who barred him. He explained that his wife was in labor and that he needed the help of a midwife.

“After almost two hours, the midwife arrived, and the delivery went well. But this was an obstacle my mother had to overcome, and I feel ashamed that she had to go through this because of me. We both suffered under these circumstances. The situation was very harsh during the First Intifada. I always ask myself: why me? Why us as Palestinians? There is someone on the other side at the same time, on the same moment, on the same day, who had a mother who gave birth with all the necessary care, surrounded by doctors and nurses, in a warm place; not like here where it was cold and where we didn’t have access to electricity to turn on the heater in case we had one. So why is that? I never find an answer to my question,” ponders Hamzeh.

The Palestinian refugee says that childhood in a refugee camp is far from “amazing.” With the place closed off by fences, frequent military incursions, no place to go, no place to play, no playgrounds, no fun. “The stereotype I have of Israel, the first image that comes to my mind when someone says the word ‘Israel’ is a soldier with a gun because I grew up between the First and Second Intifada,” he says.

The difficulties faced by Palestinians in the West Bank, however, go back well before Hamzeh’s mother’s generation. May 15, 1948, marked the life of these people. Known as Nakba Day, the date symbolizes the expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians from their lands, who, according to the United Nations, were exiled by the creation of the State of Israel, which declared its establishment unilaterally the day before, or decided to flee due to the harsh conditions they would have to face.

When talking about Nakba, Hamzeh gets emotional and remembers the life of his grandmother, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, who died in 2008. “She didn’t remember my name, my father’s name, or the life she had in the countryside. But she always remembered what life was like in the village she lived in before the Nakba, before she was expelled. And if I asked her, ‘Grandma, what’s my name?’ she’d say, “I don’t know. Is it Ahmed? Who are you?’, but if I asked what happened during the Nakba, she would start to tell you all the details”.

According to the Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights (BADIL), between late 1947 and early 1949, almost 900,000 Palestinians, representing 66% of the total Palestinian population at the time, were expropriated. 85% of the region’s indigenous population lives internally displaced in what is now the State of Israel, many Palestinians fled and became refugees in what is now the West Bank and Gaza, and others fled to neighboring countries, mainly Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan.

Amaya el-Orzza, a legal researcher at BADIL, explains the difference between internally displaced people and refugees: “Basically, both groups of people were driven from their homes. The main difference is that refugees, when expelled, crossed an internationally recognized border and therefore arrived in a different country. Internally displaced people have never crossed an international border, but they are displaced within their own country.”

With the issue of two peoples – Arabs and Jews – in the same region and the establishment of a state in 1948, a unique condition was created that only Palestinians have: that of refugees in their own territory. That is, there are Palestinian refugees who live in other countries, there are Palestinian refugees who live in refugee camps in Palestine, and there are internally displaced Palestinians, who do not have the legal status of refugees, but who were also expelled from their places of origin. Amaya el-Orzza explains this peculiarity in the video aside.

On account of this forced mass exodus, on December 11, 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194 (III), which explained ways to solve the Palestinian problem. The Assembly declared that refugees who wished to return to their homes and live in peace with their neighbors could do so as soon as possible; and that indemnities should be paid by way of compensation for the goods of those who decided not to return to their places of origin.

Resolution 194(III) is known by Palestinians as “The Law of Return,” which is applied to any refugee in the world, which, supported by the UN, defines that every person expelled from their territory has the right to return. As Amaya el-Orzza explains, in the case of Palestinian refugees, it is not only this resolution that supports their right to return.

Calling that the situation of the Palestinians expelled in 1948 remains unresolved, Hamzeh states that he always has in mind resolution 194, how it is important for him to keep it alive, to persist in the dream that one day the Palestinians will be able to return from where they came. The refugee also says that he cannot judge that no one works to make this happen and that no one will ever succeed, despite it being a very complicated situation.” It is complicated because they now have a State, they built the wall, built checkpoints, built everything. They did what they wanted to protect themselves. But Israelis don’t know who the refugees are or who the Palestinians are. Who lives on the other side? Who lives behind this wall? They do not know. So what I would like to tell them is that there is a human being here who once lived in Jerusalem, who was born there, was expelled and one day he must return to his home”.

Who Lives Behind the Wall?

Through the narrow alleys, Palestinian flags hang from the houses. The boys play football in a small vacant lot next to a garbage dump. The smell of falafel, a chickpea dumpling typical of Arab cuisine, being fried fills the tent with children who go to buy food for everyone in the family. It seems like a life like any other, but when they come home from football and falafel, the kids come across the wall. And while walking close to it, their eyes water and their skin burn, a consequence of the fresh remnants of tear gas that are thrown in the place daily.

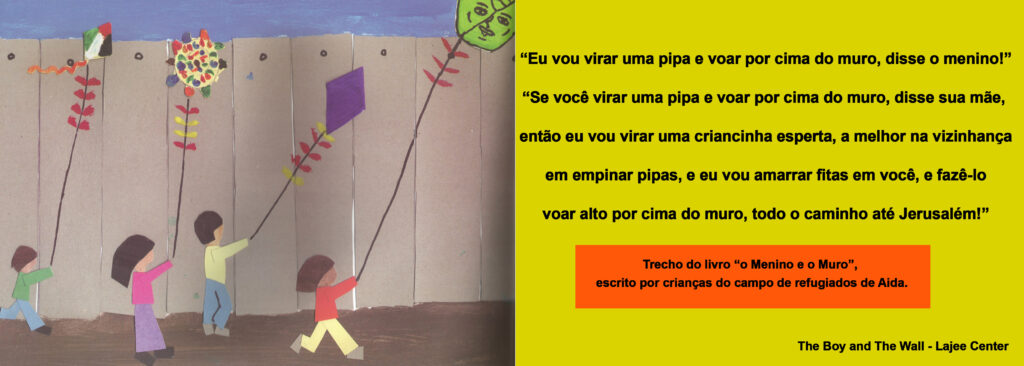

The children are among the 5,500 Palestinian refugees living in the 0.071 square kilometer Aida refugee camp, located between Bethlehem, Beit Jala, and Jerusalem. Surrounded by the West Bank Wall and close to the settlements of Har Homa and Gilo, which are illegal under international law, camp residents are often victims of Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) military incursions when there are clashes between the local population and the soldiers, leading to a steady increase in the number of Palestinians injured..

A resident of Aida, Brazilian Manuela Jorge, 28 years old, says that it is not easy to live in a refugee camp: “it is difficult because of the day-to-day since at any time the soldiers can invade or the boys will throw stones at the wall then the soldiers will fight back, or sometimes they are in training and they throw tear gas and also rubber bullets.”

Graduate in International Relations, the Santa Catarina native is married to a Palestinian refugee she met in 2013 when she went to do volunteer work at the NGO Lajee, in Aida. “I’ve always been very interested in the Middle East itself and the Palestine-Israel issue, and I came here to understand a little bit of what the media doesn’t show,” she says.

For Manuela, one of the biggest differences between living in Brazil and Palestine is the impotence of not being able to do anything. She explains that because of the military occupation, Palestinians living in the West Bank are not allowed to go to Jerusalem. Although the Brazilian can cross military checkpoints and reach Jerusalem, being international, she feels uncomfortable that she cannot do anything to change the fact that her husband and her new family cannot.

Manuela mentions in her video the brutality of the military incursions inside the Aida camp. Most of the soldiers who work in the refugee camps are young men and women between the ages of 18 and 20, carrying out mandatory military service for both sexes, with a duration of three years for men and two years for women.

Israeli activist Sahar Vardi, who refused to serve in the army because she did not agree with the militarization of society, explains that the problem lies at the root of the country’s education. “One of the objectives of the Ministry of Education is to prepare young people for military service; the army is part of the country’s identity”.

With the aim of breaking with this militarization of society and putting an end to the process of occupation of Palestine, the Israeli organization Breaking the Silence, formed by veteran fighters of the Israeli army, was created during the Second Intifada to “come clean” about what happens in the occupied Palestinian territories. The institution aims to stimulate public debate about the price paid by Palestinians and Israelis alike for sending young soldiers to control a civilian population on a daily basis.

The Wall

“It’s a fright. A huge concrete wall, eight meters high. The impression I get is that it’s going to move and throw itself onto me. It’s as if the wall was going to take the form of one of those giant transformer robots and start walking. The guardhouses are even taller and look like the robot’s head. I’ve only been standing here for a few minutes, but it feels like a long time. I think I am shocked by what the wall represents, the repression, the confinement.”

Adriana Mabília, Viagem à Palestina: Prisão a céu aberto. (Journey to Palestine: Prison in the open)

In 2002, the Israeli government approved the barrier’s construction, stating the need to prevent violent attacks caused by Palestinians in Israel. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the structure should reach approximately 712 kilometers, considering what has already been built and what is still under construction.

Concrete walls, fences, ditches, barbed wire, sand paths, an electronic monitoring system, patrolling and a buffer zone constitute what former UN Rapporteur for the Occupied Palestinian Territory, John Dugard, calls the “Annexation Wall,” which, when completed, will have 85% of its structure within the West Bank, isolating 9.4% of this territory, where there are 32 communities where approximately 11,000 Palestinians live. The infographic below shows the construction process and location of the wall.

The 2004 Advisory Committee of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) established that parts of the barrier that exist within the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, associated with the regime of mobility permits and checkpoints, violate Israel’s obligations under international law. For the Palestinian non-governmental organization Al-Haq, the wall’s construction is also a violation of the commitment that Israel made in 1995 during the interim agreement between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. According to the Al-Haq report “The Annexation Wall and its Associated Regime”, the construction of the wall in the occupied Palestinian territory (tPo) and its associated regime (such as military checkpoints, permit system, and military incursions) are having a devastating impact on the fundamental human rights of the Palestinian population living in the regions affected by the structure.

Occupation

“Legally speaking, what is happening in Palestine today is a belligerent occupation. It’s also considered apartheid, and it’s also considered colonialism,” explains Amaya el-Orzza.

Factors such as unequal rights between Palestinians and Israelis, control of movement, confiscation of land, demolitions of houses, and control of the lives of Palestinians are elements that characterize this occupation.

For the Palestinian Baha Hilo, what has been happening is a systematic shift from Palestine as home to a diverse population to a place where it is home to a specific group, Israelis Jews, who have privileges and a superior status compared to other people.

“We are in Bethlehem. Our president lives in Ramallah. There are three military checkpoints between Bethlehem and Ramallah, so if Mahmoud Abbas wants to visit Bethlehem, he will need permission from Israeli soldiers. In other words, an Israeli soldier has more authority than the president of Palestine,” explains Baha.

Sireen Khudairi, a Palestinian who has already been arrested and tortured by Israeli authorities for teaching children who did not have the legal right to go to school, remembers the psychological problems caused by the occupation: “We are still human. For me, personally, it affects me a lot psychologically, especially at night. These are scary nights to be here in Palestine, especially if you grew up in this situation.”

Sobrevivendo em área C

The Israeli settlements that surround Mohammad Kabneh’s small farm* make it imperceptible to those who come from afar. Even with a demolition order issued, without water, without access to natural resources, and threatened daily by settlers, the Palestinian lives up to the tradition of excellent Arab reception. With a red kufiya on his head, typical Bedouin attire, lots of tea and coffee, Kabneh talks about the inequality between Israeli settlers living in the settlements and Palestinians living in Area C:

“When they built the settlement here, in the place where we used to live, we were forbidden to take the animals to graze there. While we occupy – “illegally” – according to them, these small spaces, families of foreign Jewish settlers from Europe are given huge pieces of land, as you can see, to plant dates. They receive water, electricity, roads, green area, and all the necessary structure to plant. In the meantime, we need to be very careful with our animals because if they cross into their territory, they are shot dead”, he says indignantly. The settlers have gun ownership and the right to private security, paid for by the government. There is also no punishment for the death of animals or for the aggression of people who come to invade their territory.

Israeli settlements are illegal under international law and are one of the most sensitive issues in the peace process. The former spokesman for the Jewish Communities in Judea Samaria and Gaza, Bob Lang, an Israeli settler who has lived for more than 30 years in the settlement of Efrat, south of Bethlehem, explains that although the United Nations says the settlements are illegal, the Jews have the right to live in these lands. “Jews lived in this area before World War II. Then in 1948, the Jordanians expelled us, and no Jews were able to live here until Israel won the war in 1967. After that, we were finally able to rebuild our homes on this site. At that time, there was nothing here, and now we have a very well-organized community. The people who live inside are normal people like you and me: most of them go to Jerusalem every day to work,” he explains.

In the video below, it is possible to learn a little more about the problems those who live in Area C face and learn about the history of the Bedouin Jameel Jahalin.

Photos of her husband arrested without trial are all over the house, but they don’t fill Sireen’s void. “My dream is to be able to save all children, not to let them live the same situation that I lived,” says, with tears in her eyes, the 28-year-old Palestinian woman, who since 2010 has been a volunteer at the NGO Jordan Valley Solidarity, an organization that aims to protect and empower Palestinian communities in the Jordan Valley.

Located in Area C of the West Bank, the Jordan Valley is one of the most vulnerable regions in Palestine. The site is home to rural Bedouin communities and villages, a place of frequent military incursions, demolitions, human rights abuses, and deprivation of resources and services.

Four years ago, Sireen started teaching children in the region, as there are no schools for Palestinian children there. “We started by building ten schools and teaching classes, but we saw that it was not enough, as these children needed to be encouraged to have hope for a future. We are now building the first library in the Jordan Valley and also teaching theater, music, and dance classes. We hope that these initiatives help these children to express themselves,” she explains.

Hope

“Israelis are motivated by fear,” says Nitzan Horowitz, a politician, and journalist, who is a former Meretz deputy in Israel’s parliament and now the chief US correspondent for the Israeli news company, Channel 2. For him, the solution to the Palestinian question will only come with a leadership change on both sides, as the resolution depends on both sides. “Oslo was a good initiative, too bad it didn’t work out in practice,” he says. Horowitz explains that he is against the occupation because if it is maintained, Israel will not be the Jewish and democratic state it purports to be. “I believe in education and dialogue,” he explains.

“No hate,” writes Hamzeh. He underlines and circles it several times. “I teach them, the children I work with, not to hate. That’s a yes to hope. A yes to hope. Nobody loses hope in this country. Nobody. We work with children because they are the basis of society. And yes, we all have hope. We’ve all kept hope alive for a long time. That’s why we’re still alive.”

* Mohammed Kabneh is a fictitious name to protect the interviewee’s identity.